SIR PETER LELY

(1618– 1680)

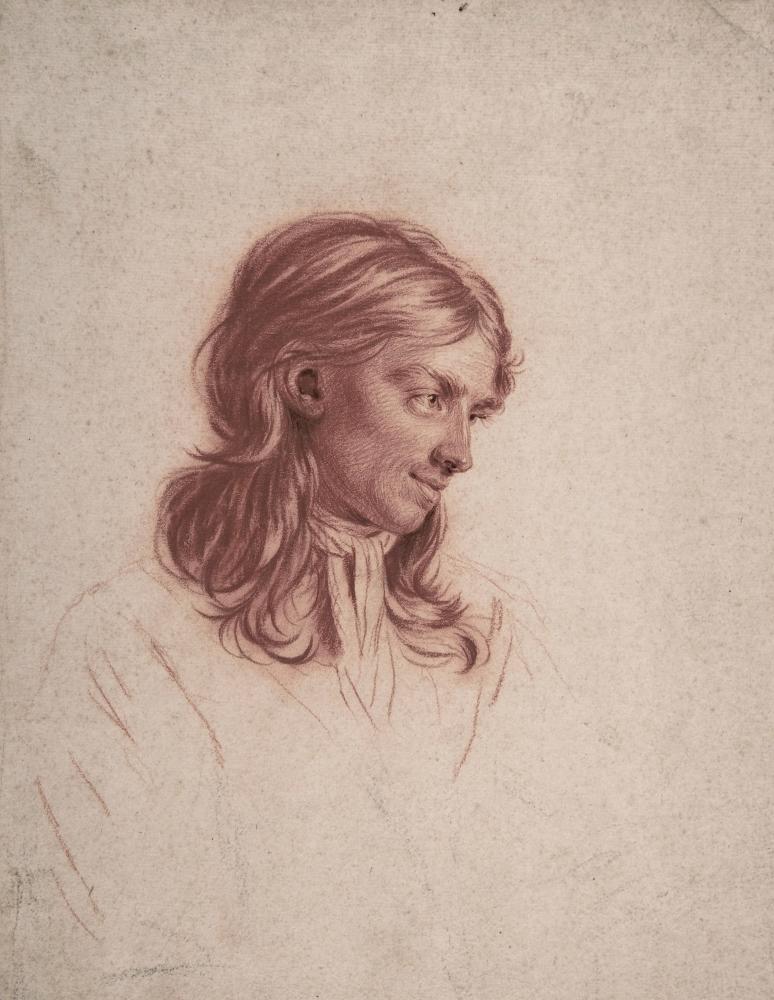

Portrait of a Gentleman

Sold in association with Day & Faber Ltd

Provenance

Private Collection, France

Among Sir Peter Lely’s most beautiful and rarest works are his highly finished, signed portrait drawings, which he made as independent works of art. Shortly after his death in 1680, his executor Roger North listed the contents of his studio, prior to an auction, and recorded a group of such drawings, which he described as ‘Craions’, noting that they were ‘in Ebony Frames’,[1] which suggests that they were accorded the status of paintings and hung as such. This may account for the fact that so few have survived, for most will have faded away after sustained exposure to light. This sheet, by contrast, has survived remarkably well, having suffered very little fading or abrasion: the white highlights that animate the drawing, enhancing both the textural contrasts and the strong sense of chiaroscuro, are as well preserved as one could hope. All too often, only the faintest suggestion of such modelling survives.

Lely’s technique in such drawings appears to have been novel to his contemporaries, even to the extent of having to have his chalks specially made to his requirements. The scientist Christiaan Huygens (like Peter Lely, a Dutchman), who was in London in 1663[2], took the opportunity of going to Lely’s studio and described his visit on 22 June to his brother Constantijn, when he was especially impressed by the artist’s portrait drawings, asking him about his methods and materials[3]. He noted that Lely restricted the use of colour to the face alone, using it very lightly, and described the paper he used as ‘un peu griastre’, which probably simply meant somewhat neutral in tone.[4] Returning to the studio a week later, Christiaan wrote in his uniquely Anglo-Dutch French that ‘Lilly ne m’a pas encore donné sa recepte pour le pastel, parce que je ne l’ay trouver chez lui depuis, ou bien s’il estoit, there was a Lady sitting.’[5] He finally succeeded in getting Lely to discuss his pastel technique on 13 July and visited the man who made his chalks a few days later, going on to describe the process in great detail, noting that the finished colours were carefully made so that ‘it is easy to write with these sticks on paper, and they never become hard.’ He concluded by telling Constantijn that in addition to talking about his own drawing technique, ‘Lilly showed me his Italian drawings which are all exquisite.’ [6]

While Lely habitually made preparatory studies for his own or his studio assistants’ guidance in developing poses for sitters or for details such as the fall of drapery or the treatment of hands in his oil portraits, his portrait drawings were not related to commissioned portraits on canvas. Their intimacy and perceptive grasp of character seem on another level from the generally more conventional and less probing nature of the oil portraits. The most powerful of his drawings are those of sitters whom he knew extremely well, like Sir Charles Cotterell (in the British Museum), or – perhaps most striking – himself (Private Collection). The present drawing conveys such immediacy (and perhaps a hint of vulnerability) that it is tempting to think it is also a self-portrait. The angle at which the head is shown makes it difficult to draw direct comparisons with either the drawing of c.1660 or the painted self-portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London, of around the same date, but the similarities are certainly striking.

Both the present drawing and the self-portraits in the NPG and in a private collection show the sitter wearing the dress and hairstyle of the early 1660s. The length of hair, its fullness and the carefully curled fringe are characteristic of that date, while the narrow ‘pencil’ moustache is also a fashion of the late 1650s and early 1660s. In both drawings, the sitter gestures towards himself with his right hand, as if suggesting a degree of self-knowledge. This pose echoes – consciously? – Van Dyck’s self-portraits, in particular the Self-Portrait with a Sunflower, engraved by Hollar in 1644, which was conceived as a grandiose form of self-advertisement. Lely’s self-portraits were less blatantly self-promoting, but his splendid manner of living – Samuel Pepys noted ‘a mighty proud man he is, and full of state’ – was probably a conscious emulation of Van Dyck, whom Lely greatly admired both for his art and for his gentlemanly existence.

Whether or not this is a self-portrait, it is unquestionably a drawing of great immediacy and presence, surely representing if not Lely himself, then someone in his closest circle. Its psychological intensity makes it among the most remarkable drawings of the period.

The drawing will be included in Diana Dethloff's forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Sir Peter Lely's work.

Lindsay Stainton

[1] ‘Sir Peter Lely’s Collection’, editorial in The Burlington Magazine, LXXXII, 1943, p.188.

[2] His visit was largely connected with his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society, but he was interested in the broader cultural life of London, and doubtless had an introduction to Lely.

[3] Oeuvres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, The Hague, IV, 1891, pp.361-2.

[4] Huygens, op.cit., p.371

[5] Huygens, op.cit., p.363, 29 June 1663.

[6] Huygens, op.cit., pp.370-1. By the time of his death in 1680, Lely’s collection of Old Master drawings and paintings was prodigious.