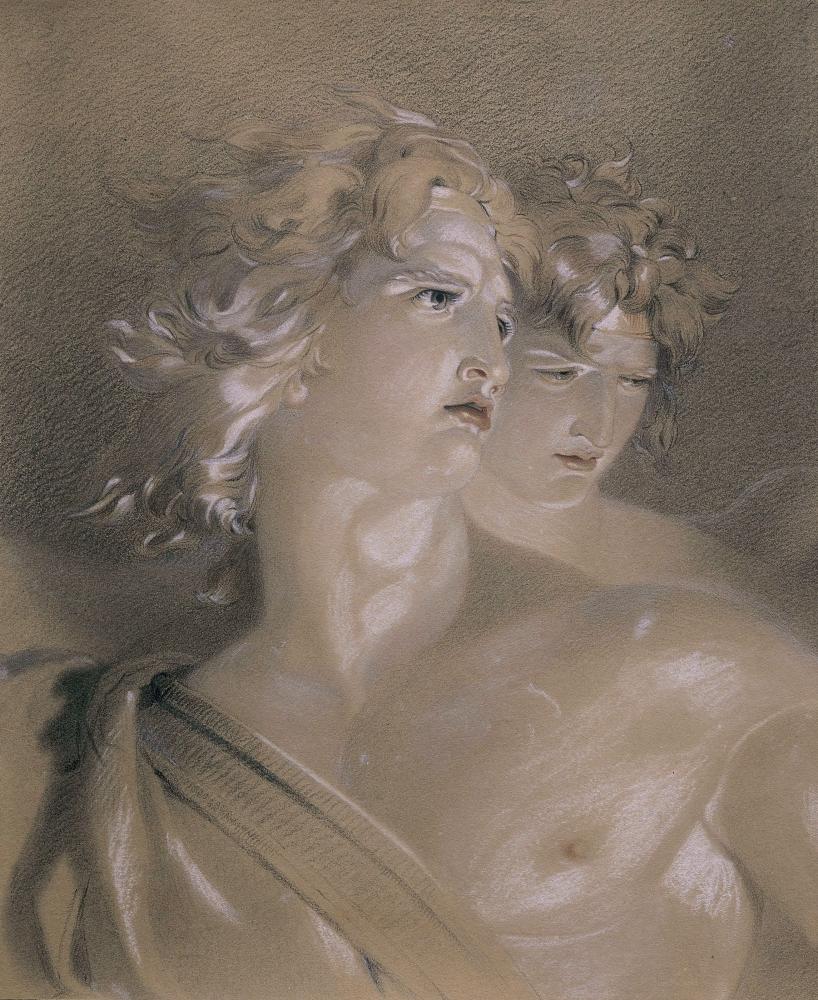

RICHARD WESTALL R.A.

(1765-1836)

Satan Exulting

Engraved by F.P. Simon for J.& J. Boydell, 1794

Provenance

Private Collection

John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, composed c.1650-60 and first published in 1667, was a work concerned with rebellion, and Milton himself had been a republican, writing at a time of political upheaval in England. While Jonathan Richardson had recognised the Sublime conception of Satan in his Explanatory Notes and Remarks on Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1734, it was Edmund Burke in 1757 who identified Satan as the epitome of the rebel and the independent symbol of the age, and Milton as the English poet most capable of evoking the Sublime in pictorial fashion: ‘In what does this poetical picture consist? In images of … an archangel, the sun rising through mists, or an eclipse, the ruin of monarchs, and the revolutions of kingdoms’. In painting, it was not until the 1770s that artists began to depict Satan as other than evil and ugly, to be despised as well as feared, but Henry Fuseli (1741-1806) and, surprisingly, J.R.Cozens (1752-1797), were among the first to show him in heroic guise, thus anticipating later representations of him in this role.

Fuseli’s devotion to Milton, and his depictions of Satan as an Apollo-like figure, were highly influential, and in the 1790s he was to paint a sequence of more than forty pictures on Miltonic themes. Milton’s conception of the heroic splendour of the rebel, regardless of what he might represent, acknowledged the notion of the flawed hero, who was nevertheless preferable to those who strike compromises with the powers of this world. Such a view captured the imagination of many, especially at the time of the French Revolution; at this moment of crisis, the figure of Satan as the embodiment of spirited revolt took on an added lustre. This is perhaps what Blake meant when he noted approvingly of Milton, ‘He was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it’.

Subjects of this sort were ideally suited to a generation of artists attuned to new Romantic ideas of the outsider as hero and the importance of individual genius. It is no surprise that besides Fuseli, the Irish history painter James Barry (1741-1806), one of the most original talents of the period, was attracted to Milton’s Satan on several occasions; his etching Satan and his Legions Hurling Defiance toward the Vault of Heaven, c. 1792-4, may have influenced Westall. However, although Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) was among Fuseli’s greatest admirers, it is more surprising that he – the most successful portraitist then practicing – should have exhibited an enormous painting of Satan Summoning his Legions at the Royal Academy in 1797 (where it was badly received). As well as the chance of attempting the grand and sublime, such subjects offered an unparalleled opportunity to depict the heroic male nude, which had always been at the centre of the academic tradition.

Richard Westall’s elegantly powerful watercolour may be dated c.1794, when it was engraved for Boydell’s illustrated edition of The Works of John Milton, the peak of the fashion for works inspired by Paradise Lost. Here the artist conflates several passages from Book I; with Beelzebub beside him, Satan stands at the edge of the sea of fire, addressing the fallen angels:

He call’d so loud, that all the hollow Deep

Of Hell resounded…

Satan is shown in the Romantic heroic mould in a Sublime, fiery Hell, an idealised figure in foreshortened close-up to enhance the dramatic tension:

…he above the rest

In shape and gesture proudly eminent

Stood like a Tow’r; his form had not yet lost

All her Original brightness; nor appear’d

Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d, and th’excess

Of Glory observ’d…