ANTON RAPHAEL MENGS

(1728-1779)

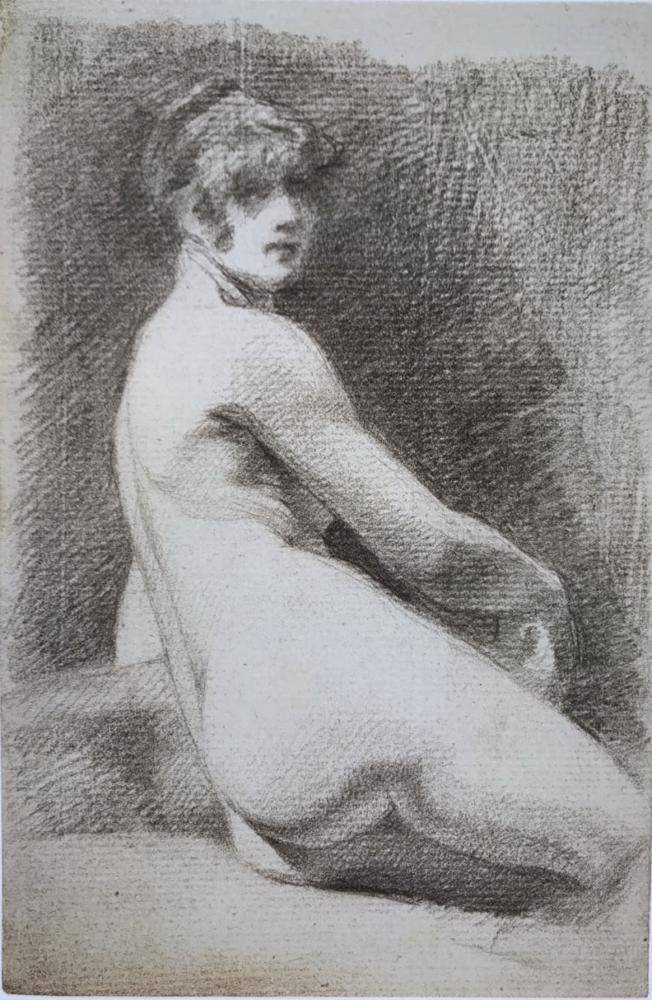

Seated Male Nude

Sold in Association with the Nicholas Hall Gallery

Provenance

Bears unidentified collector's mark, lower right (L.619a)

Private Collection, UK

Literature

To be included by Dr. Steffi Roettgen in the next supplement to her catalogue raisonné of the artist's drawings.

Anton Raphael Mengs’s father Ismael (1688-1764), a somewhat obscure portrait painter employed in the Dresden court, was resolved to make his children into artists of world renown. Described as “a true goth and a vandal” - Ismael presided over a tyrannical academy, where his children were taught from dawn to nightfall the rudiments of drawing, geometry and the unremitting practice of copying Old Master prints. To nurture flawless drawing, Ismael would place his child’s drawn copy on top of the print and compare the two on a light-filled window, errors were marked in red and for each mistake the child would receive a strike from the whip. One of Anton’s sisters, attempting to escape their father, broke her leg from vaulting through a second-floor window; later another son ran away to train under the Jesuits. Nonetheless, Ismael succeeded in his objective with Anton, who by the age of twelve had become an acclaimed artistic prodigy. After further training in Rome, specifically drawing the male nude under the instruction of Marco Benefial (1684-1764), Mengs ‘was ultimately to develop into one of the great draftsmen of the eighteenth century.

The present academie drawing, which dates to the mid-late 1750s, is a superlative example of the artist’s life drawing. A pictorial summation of an unceasing investigation into the aesthetics of the male form, refined by recent study at his own private academy - the école de Mengs in Via Sistina - and at the newly established Accademia del Nudo on the Capitol, where Mengs in the mid-late 1750s was one of the school’s principal teachers.6 The drawing retains lines of communication back to the early studio academies of sixteenth century Florence and Rome (Accademia di S. Luca), the Carracci school in Bologna, and through to the later virtuosi of Italian life drawing: Guercino, Cortona and Bernini. The study’s singular synthesis of anatomical exactitude and ideal form exemplifies Mengs’s devotion to ‘il vero’ (the perfect imitation of the true)- a dictum which he regularly recited to his students; this is the artist at his most technically assured, where form and subject are one, and in the words of Mengs, a proficient exercise in ‘the understanding of the bones and muscles, and a workmanship to be admired in whatever place and under whatever light'.

The école de Mengs was located on the Strada Vittoria, which today would be 72 Via Sistina, a couple of hundred metres from the Spanish Steps. From the early 1750s until close to the end of the decade Mengs rented this large house as a site for both his spacious studio and as living quarters for his young family. Until his death in 1749, the second-floor of the house had been occupied by the French artist Pierre Subleyras (1699-1749), and it was on this storey where Mengs’s studio and private academy operated from. A painting by Subleyras shows a section of the central room as high, spacious and full of light, and, we know from contemporary descriptions that the floor also contained separate spaces which were used as smaller private studios. One of these rooms housed Mengs’s important collection of plaster casts, which the artist had made himself from a wide but discriminating selection of antiquities. These fragments of heads, bodies, feet and hands were positioned under a large skylight, and, artists from a range of nationalities, ages and abilities would use these casts to draw anatomical studies. The casts acted as a suitable contingency in lieu of a nude model, which the Papacy forbid the use of in private studios, a regulation which Mengs scrupulously adhered to. Access to Mengs’s substantial collection of engravings was encouraged and these were pored over under a backdrop of informal discussions about artistic methods, theories and each other’s drawings. Although Mengs was occupied for much of the day in his own private studio, the artist Laurent Pécheux (1729-1821), later related that Mengs would offer advice and occasionally correct the students drawings as he crossed the cast room to his own studio. Johann Wilhelm Beyer (1725-1796) observed that Mengs “in the evenings, when he no longer had sufficient light for his work, used to come to us to study, and spend an hour to talk about an article of art.” Notable British artists that attended the école de Mengs during these years include Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798) and Nathaniel Dance (1735-1811). Indeed, in 1759, Hamilton as Mengs’s successor, rented the second floor of 72 Via Sistina. From 1782 until her death in 1807, Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and her husband Antonio Zucchi (1726-1795) lived and worked here.

Pécheux and other students of Mengs frequently remarked on the artist's impressive ‘didactic inclination’, and this propensity was given greater scope after Pope Benedict XIV founded the Accademia del Nudo on the Capitol in 1754. The academy was ‘freely accessible and free of charge’ - Mengs was one of ten professors, and the only non-Italian, to instruct, direct and lead the teaching programmes at the Accademia del Nudo. In 1755, Mengs was among the first professors to lead a teaching cycle, and he ‘devoted himself assiduously to improving the study of the nude and modernising the pose repertoire.’ Interestingly, Dr. Steffi Roettgen has revealed how Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) attended this first teaching cycle of Mengs’s in 1755. The present academie study was almost certainly drawn by Mengs at the Accademia del Nudo during this period. Such a date is supported by both the inscription, and, the style and technique of his draughtsmanship.

An almost identical academie drawing by Mengs - in spite of the fact that the body of the model is reversed along the horizontal axis - is dated 1755 and uses the same sized paper. After 1755 there are scarcely any extant nude drawings by Mengs using red chalk on white paper, the typical medium and material used for academies. Two 1775 red chalk studies of nudes do however survive in the Brera Academy, Milan. This signals a change from the 1740s where Mengs’s use of red chalk appears to predominate, from what one can judge by the surviving drawings, including, a group of drawings now in the Albertina, Vienna. Acknowledging this simple chronological framework, it is conceivable to hypothesise that the present academie drawing dates from 1754-55, when Mengs had the opportunity to draw from a live model again - indeed the same model and pose that was used in the 1755 drawing - but before he had completely transitioned to using black or grey chalks as his chosen medium for academie drawings.

It was one of the singularities of drawing from the academy model that ‘the master in charge set the pose in such a way that it corresponded to his ideas and his concept.’ The particular pose found in the present drawing is sophisticated, dynamic, and unusual; the complicated foreshortenings and profile of the lower arched foot indicate a form that was challenging to draw. The sweep of the athletic back hints at the finely wrought grandeur of the Belvedere Torso, the leichtigkeit (lightness, delicacy) of which Mengs greatly admired. As one of the pre-eminent 18th century treatise-writers, Mengs’s understanding and theories on formal values were in the words of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), replete with ‘deep observation and luminous perspicuity’. ‘The simplicity of contour’ which Mengs extolled as a fundament of Greek art is seen in the naturalistic but not unidealised execution of the present nude. The morbidezza (the soft delicacy of flesh) manifest in the detailed musculature - which Mengs eulogised in his writings on the Apollo Belvedere: 'the finest exemplar of beauty we have’ - emphatically eschews ‘realistic detail such as veins, sinews and folds of skin which he [Mengs] criticised in modern sculpture’. Body positions were often selected from a ‘canon of poses’, an imaginative anthology in most cases, amassed from prototypes of ancient sculpture to model books, but, less ordinarily from paintings.

Poses were often variations of a type, to differing degrees, and very occasionally absolute inventions. The present pose as mentioned already is singularly uncommon. A Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669) nude study now at Düsseldorf is not dissimilar in the lower half of the model’s configuration. Closer still is the bronze Seated Hermes, found at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum in 1758, housed today at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, whose discovery may feasibly just have predated Mengs’s drawing. Little more than just an interesting comparison with the general form of our drawing is the pose and angle of the seated nymph in Titian’s Le Concert Champêtre.

The vibrancy of the red chalk surface outside and around the model’s figure, both in the cast shadows and almost uniform background of softened chalk shading, are formed by parallel hatching; the cast shadows being made from a pattern of sharper visible strokes with wide intervals of space between each line, while the background combines multiple thinly-spaced, soft parallel lines over what appears to be large areas of a lightly applied stumped chalk shading. The light source in the setting (probably a studio lamp) is positioned above and to the side of the model. The vertical illumination not only enhances the relief of the figure through a distinct contrast of light and shade but also allows for certain pronounced parts of the body: left shoulder, a band running from the left part of the pelvis down into the thigh, the left triceps, both kneecaps, to coruscate as points of concentrated reflected light, shown by Mengs with white chalk. Nonetheless, whether in light or shadow, all the regions of the body are legible and clearly defined. The internal modelling of the body, constructed through the irregular strength, and clear separation, of falling light, allows for interesting shapes and patterns of abstract forms to configure: in particular, the dark triangular nape of neck set into the long curving ridge of the spine, and the striking shape formed by the aperture between the top of the right thigh, underside of the left foreshortened arm, in conjunction with the jagged contour caused by the miniature peaks and troughs of the left abdominal and pectoral muscles. A triumphant note of this study is the ‘clear indication of bone structure and the correct differentiation between muscles in action and at rest.’